How Players and Mathematicians in Leiden Look At Chess

To some, chess is a game. To others, it's a scientific puzzle to be solved. We dive into both these worlds by talking to the experts!

The history of chess begins in 600 BCE in India. The rules evolved, the game became a competitive mind sport, and strategic thinking changed continuously. But none of those developments had as great an impact as the introduction of the computer, which inextricably linked mathematics and computer science with chess. Today we look at that scientific side of chess by talking to Leiden computer scientists who used games for physics research. We also talk to Leiden's very own Beth Harmon , faculty (and Dutch) chess champion Timardi Verhoeff, about her victory in the recent Leidsche Flesch chess tournament.

Solving Chess

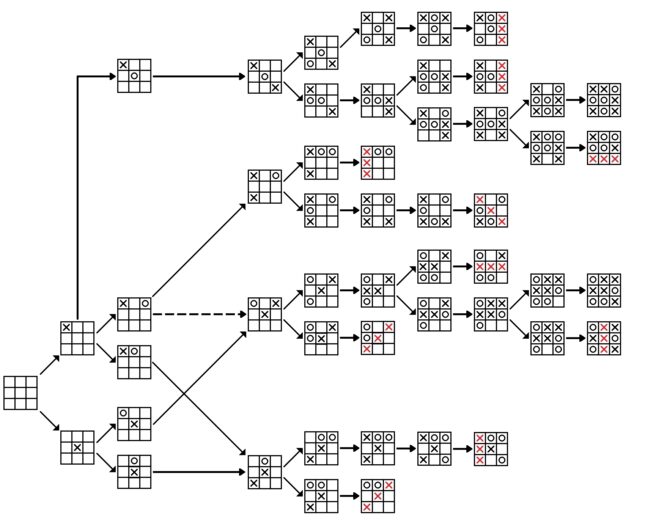

Computer scientists and mathematicians look at a chessboard a little differently than the average player. They see interesting scientific challenges, such as the stubborn question, "Can we predict who will win this game?” It may sound strange, but in principle it should be possible: just think of a game like tic-tac-toe, for which you can draw out every possible game (if you have the time). You will then come to the conclusion that players with perfect strategies will always play to a draw.

The difference with chess, of course, is that many more outcomes are possible. It is relatively easy to calculate that after just four moves by white and black, almost two hundred thousand different positions are possible. In fact, considering how long an average chess game lasts, and taking into account how many moves are possible on average per position, mathematicians have calculated that about 1046.7 different games could be played.

If we look at how "classical" chess computers work, we conclude that even with their help we will not be able to predict the outcome of a chess game anytime soon. This is because those computers use their computing power to calculate and evaluate millions of moves and possible positions per second. For example, a chess computer like Deep Blue used this “brute force” approach to defeat then world champion Garry Kasparov in 1997. But for the desired proof, this “brute force” method is simply not well suited: such a program unfortunately cannot calculate 1046.7 different games, and so “solving chess” remains an unsolved problem.

Chess and High-Energy Physics

Now you may be thinking: that's too bad, but...what does it matter? Chess is still just a game, so the success or failure of a chess-related research project is not important, right? The opposite has been proven by the work of HEPGAME (High Energy Physics Game), a collaboration between Nikhef (Dutch National Institute for Subatomic Physics) and Leiden University. The research group recognized that the various algorithms used to find optimal moves in games like Chess and Go could also be used in high-energy physics. When we asked Professor Aske Plaat, himself a "HEP gamer," about this, he said, "In the enormously complex calculations of high-energy physics, we find equations and formulas of literally Gigabytes and Terabytes in length. A very specialized formula manipulation program, FORM, has been written to simplify these equations."

Searching for the best formula manipulations, like finding the best chess move, is a matter of scouring through branching options for an optimal path. That's where Professor Jaap van den Herik could help the team with his knowledge of algorithms. After all, he won the Humies Award for Evolutionary Computation in 2014 for an innovative chess computer he programmed. With this convergence of expertise, the researchers were able to make FORM function many times more effectively, bringing the importance of game algorithms beyond the 64 squares of the chessboard.

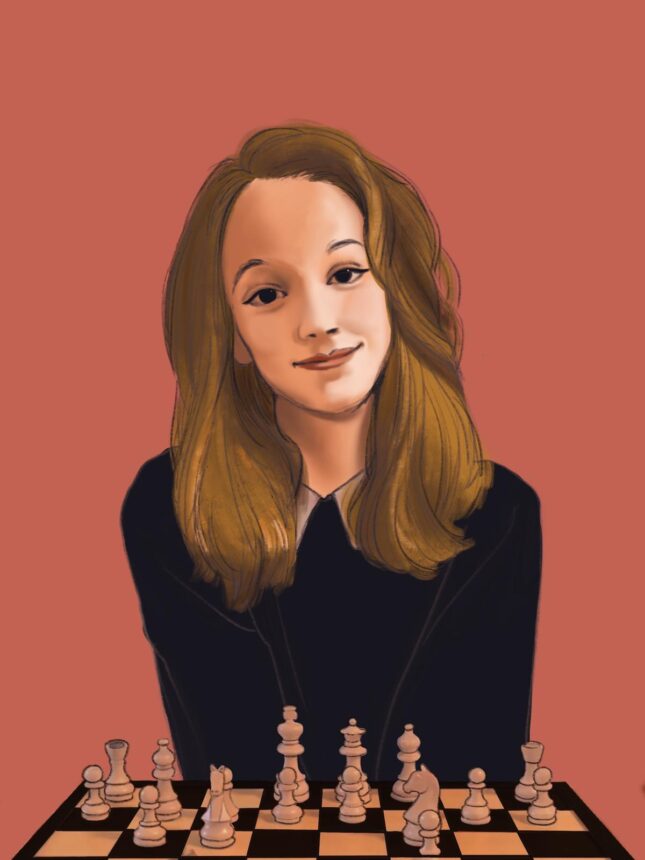

In Conversation With Timardi Verhoeff, Science Faculty Chess Champion

In the end, the mathematical aspect of chess remains only half the story. For most, the main charm of chess is the psychological or human aspect of the game. That's also the case for Timardi Verhoeff, who won the 2021 Leidsche Flesch Chess Tournament last week. "Sometimes you think you're going to lose, but you can still make a miracle happen. If you don't give up, anything can happen, and that's what I find so interesting about it."

The most enjoyable tensions in chess come from the fact that everyone is unquestionably attached to their own ingrained style of play. "Normally I do play it safe, by building up quietly and winning in the endgame," Timardi says of her own style. She is not just any old player either: she learned the game at age nine and won the Dutch Chess Championship twice, which led to her representing the Netherlands on the European stage. All the more impressive that the tournament was filled with formidable opponents, according to her. So there are plenty of strong chess players in our faculty! The tournament could be held monthly rather than annually due to the increasing enthusiasm.

Wondering if you would also stand a chance at winning the coveted challenge cup? Then take a look at the chess position below. In this explosive situation; it is black’s turn, playing against none other than Timardi. And although this is a match between two people, we also have a computer on our side telling us that white is winning here. But there is hope: can you find the move that will put black back on equal footing with our champion? Below is the answer, in Timardi's own words.

Answer:

"The correct move is Queen to B5. The smoke is then cleared and the game is equalized. Black now has the opportunity to move forward and has regained the initiative, whereas before it was on white's side."

0 Comments

Add a comment