The Mummy or The Matrix - why not both?

Anyone who thinks that Archaeology is an out-of-date science where one only uses a shovel and brush to search for artefacts from a bygone time has not dug deep enough.

The research of digital archaeologist Wouter Verschoof-van der Vaart at the University of Leiden reveals new insights into ancient human activity through the use of both cutting-edge computer technology and the 'wisdom of the masses'. 'For example, it seems that it was much busier in the Netherlands during the Iron Age than we could previously have predicted on the basis of excavations.'

The type of archaeology that Wouter is involved in does not look underground but takes an aerial view. ‘Many places are difficult to see from the ground, or harder to access due to forests, for instance. From the air, you can map the landscape in an easy way and on a large scale. Aerial photography in itself has been around for a long time. Photos taken from an airplane have been available since the First World War. Thanks to newer techniques such as Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) we can now make a very detailed elevation model of the entire landscape which allows you to look through the vegetation.’

This does, however, result in large amounts of data. In the last two years, the provinces of Utrecht and Gelderland have collaborated with thousands of volunteers, who participated in the project Heritage Quest. In this project, the participants marked the online maps, made with LiDAR, for locations where they expected a historical find. 'Within twenty-four hours of putting the 350 square kilometers of Utrechtse Heuvelrug online, we were already done with the analysis', Wouter sighs. 'If I would have to look at all that on my own, it would have taken me years.’

Burial mounds

After a short training, the amateur archaeologists can start identifying, for example, hollow roads. ‘These are traces of the routes that carts rode through in the Middle Ages. Contrary to Roman times, there were far fewer fixed roads, but you can see that people repeat the same routes over the years due to the presence of streams and hills.’ When a participant sees such a sunken road, they can mark it. These data then accumulate, after which Wouter can use them to look back in time.

‘Then we see, for instance, that there are a lot of cart tracks in one place just before the border with Germany. Then you wonder why they used that route. After confirmation based on archive material, we now know that there was a very large inn there, a bit like how we now stop at the gas station just before the border.' Other artifacts found there can be as old as 5000 years. For example, many possible barrows are marked. These are small round mounds raised by people to bury someone. ‘When we do the hand drilling during the fieldwork together with students and volunteers, we check whether it is real.

Celtic fields

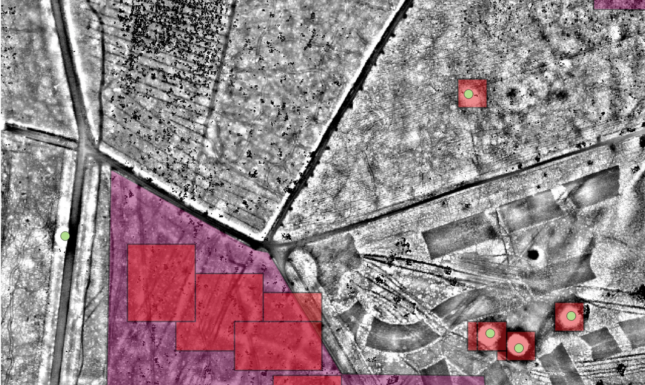

Another interesting example involves the Celtic fields, characteristic remains of fields from the Iron Age (around 500 BC) similar to a checkerboard, which are often well marked after just one click.‘These field patterns say something about the amount of food which was available at that time, and thus reflects the number of people living in that area. It now appears that the size of the populations that we can calculate with this method does not correspond at all with the models that are based on found houses or graves. In that way, with this technology we get different information, such as the amount of people or the way in which they have moved in the landscape.'

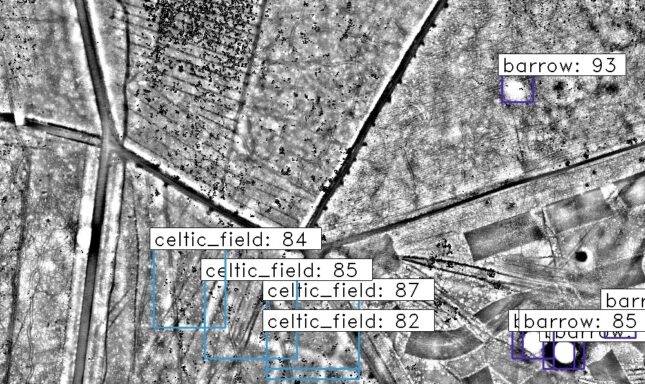

Now, you may wonder if that can’t be done even faster. During his PhD research, Wouter looked at whether it’s possible to automatically detect whether something is an archaeological structure with so-called Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) in the LiDAR data. 'Such a CNN looks for a certain pattern that we teach the algorithm. But it turned out that the distinction between, for example, a barrow or a roundabout is difficult to make. Based on the context, such as the four roads leading to a roundabout, people are able to place an object in its environment more easily. However, CNNs make fewer mistakes and can dig through the data much faster. You actually get the most complete picture through the collaboration between people and computers.’

This combination of technology and citizen science is paying off. The second of February Wouter will need to defend his PhD thesis. But he is not yet finished with the subject. 'The method can also be used in biology when counting penguins from the air, for example. And the new 'Scars of War' project will start in January, in which we will look at traces of the Second World War. We already know quite a lot about this period from other sources, and now it seems that the Veluwe is completely full of trenches, bomb craters or old ammunition depots. In this project we are going to use the same combination again to map these out too.’

The Heritage Quest project is a collaboration of (governmental) agencies and universities. Besides Wouter, researchers Dr. Quentin Bourgeois, Dr. Eva Kaptijn, Dr. Karsten Lambers, Roel Kramer and Anton Cruysheer and thousands of volunteers contribute to the project.

0 Comments

Add a comment