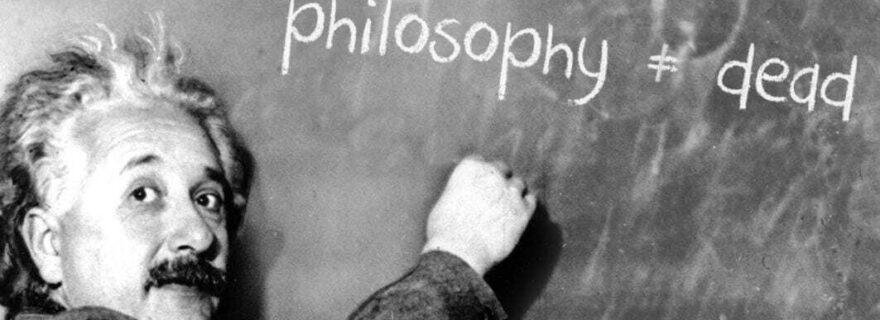

Why philosophy isn't dead: A conversation with James McAllister and Vincent Icke

Sometimes we think that science has taken the place of philosophy. To see if that's actually the case, editor Bàrbara Levering talks with none less than James McAllister and Vincent Icke.

In 1944, Albert Einstein wrote a letter to his fellow friend Robert Thornton in which he said,

“A knowledge of the historic and philosophical background gives that kind of independence from prejudices of his generation from which most scientists are suffering. This independence created by philosophical insight is - in my opinion - the mark of distinction between a mere artisan or specialist and a real seeker after truth.”

- Albert Einstein in a letter to Robert Thornton, 1944

Half a century later, Stephen Hawking proclaimed philosophy dead with these words:

“Why are we here? Where do we come from? Traditionally, these are questions for philosophy, but philosophy is dead. Philosophers have not kept up with modern developments in science. Particularly physics. Scientists have become the bearers of the torch of discovery in our quest for knowledge.”

- Stephen Hawking during the Google Zeitgeist Conference in 2011

Perhaps Einstein was talking about philosophy more generally, and Hawking's stance was essentially a bash against metaphysics - but the tone of their words clearly reflects the value they saw in philosophy itself.

Many other popular physicists join Hawking in the “cancelling” of metaphysics, such as Lawrence Krauss and Neils deGrasse Tyson. And this seems to be a common view within the scientific community. “In short, I do think that academic philosophy is undervalued by most practitioners of the physical sciences. They see philosophy as similar to poetry or to music composition: extremely valuable, culturally” professor of Theoretical Astronomy at Leiden University, Vincent Icke, tells me when I ask him about the issue.

Physics and metaphysics: why we need them both

This quickly raises the question, do these scientists have good reason to claim this? Are their positions justified? It is hard to believe that such great minds would diminish philosophy so lightly if it weren’t for good - and meditated - reason. But perhaps this is too optimistic. “I think to some extent, this is an unjustifiable stance that Hawking and others have taken with respect to philosophy. To some extent it’s just based on ignorance of philosophy and of the history of the sciences”, Professor of History and Philosophy of Science at Leiden University, James McAllister, tells me. But he is quick to mention that this is not at all odd, the fact that a specialist in physics wouldn’t be up to date with what’s happening in the fields of metaphysics or philosophy of science, and that they can’t be blamed for that. “But if that’s the case, and if you have enough self reflection and self criticism and you recognise that you might not be the world’s greatest expert in a field, then you’d hesitate to make pronouncements of the use or not of said field”. Perhaps this lack of humility can be explained by physics seemingly being at the top of the pyramid when it comes to the different scientific disciplines. It is true that these kinds of views are mainly expressed by physicists - at least publicly - and not so much among chemists or geologists, for example. “There’s a widespread feeling within the scientific community that we do have a top science. And that top science is physics,” says McAllister, “and so I think there are, to some extent, aspects of intellectual certitude or intellectual self confidence that physicists - and especially theoretical physicists - have, and which help to explain why they think they have the license to talk about everything and the foundations of everything”.

But the question remains as to why these physicists do have such negative views on philosophy in the first place. “From having talked to Stephen and other people, like Tyson, I have the impression that they are throwing the baby out with the bathwater” says Icke. “Very often philosophers have written things about the physical world - say, Nietzsche or Schopenhauer. And it’s similar to what you find in many religions, that they say something about the way the [physical] universe works. Well, these people know nothing whatsoever about the way the universe works. But questions such as, how do I know that something is true or not? What is the nature of argument, etc, that is a drastically different thing, and philosophers have sensible things to say about that”.

There’s no doubt that a lot of questions that were once part of metaphysics - questions about the existence and nature of ultimate components of reality - have been answered by science; and that most of us will value answers that come from a rigorous empirical enterprise over answers that someone concludes mainly on the basis of deep reflection and thought. But does this mean that metaphysics has come to an end? The answer is most likely : ‘no’. “ There’s always a residue,” McAllister says. Once science has answered many of these metaphysical questions, there’s still a small residue, “and that residue is always the hardest nut to crack”. Science will tell us what it is that happens. But there are further things we need to clarify to really understand the world. “What is a cause? How does a cause relate to correlation? What more do we need to read in a law of nature, in the mathematical equation, to be able to speak of a relation between cause and effect? Those are questions that aren’t tackled by physicists but which our understanding of physics depends on to a large extent.” And it may not be in the realm of science to answer them, but they still need to be considered, because they are fundamental. McAllister makes it clear that we need the addition of metaphysics to tell the story about what the universe is really like and not just have a purely instrumental account for it. “There are criteria for deciding, at least tentatively, whether a certain story, a certain account of the universe is adequate or not. One, of course, is empirical adequacy. But the second is intelligibility. When we have a demand for a story, what we are really asking is a story that makes sense to us”.

An example from the quantum revolution

Take quantum physics for instance. In its early stages, the equations were coming out well; the theory was good at accounting for observations. But there didn’t seem to be a story yet that the theory could offer us about the world, which led some physicists - such as Einstein or Schrödinger - to be suspicious of it. “Einstein, because the theory didn’t seem causal or complete, Schrodinger because it didn’t seem visualisable.” But nowadays, quantum theory paints a better picture of how the world is: it gives us a story. A strange one perhaps - if compared to “the world of everyday experience of macroscopic bodies and small speeds” as McAllister puts it - but still an intelligible one. And as Icke remarks: “All of physics is weird, except that you get accustomed to it. Everything, when it is more than one or two steps removed from your direct physical contact, is weird.”

This stage in the history of science - the quantum revolution - is also a good illustration and proof that physicists and philosophers have needed one another in their attempts to understand the world. “At that time, you saw philosophers moving onto the area of the domain of physics and physicists moving onto the domain of philosophy. It was a continuum”, says McAllister. And not just that: we also see how physicists were inspired by reading the works of philosophers. “If you read the works of Niels Bohr, as he was struggling, together with Einstein and others, with the lineaments of this radically new theory, at the beginning of the 1920s… you see him appealing to classical philosophers like Immanuel Kant, as well as modern philosophers, in order to come to grips with these puzzles”. Looking back, you find many instances where philosophy has contributed to the progress of science, in many different ways; particularly, in times of crisis or deep controversies between different scientific paradigms.

Philosophy keeps up even if we are not looking

There’s progress in philosophy, just like there is in science. Both Icke and McAllister are very firm about this. Of course, the way “progress” is made in each field is very different. But one can’t deny that new questions and considerations emerge in philosophy to reflect the current times and issues, which build upon theories and thought of previous times - something which can fit precisely into the definition of progress. It is unclear then what Hawking was referring to when he said that philosophy hasn’t kept up with the progress of science; if anything, we live in a time where philosophers of science know more about science than probably any time before - as McAllister explains - which shows that they most likely are keeping up.

There is a lot more to the story; and I am sure there is also a lot more to what Hawking was saying, too. But I still think that Einstein had it right when he said that if what we are after is truth itself, we need to broaden our scope. Science, just like any other discipline, is embedded in a context, with a history that is part of the full history of thought. Philosophy of science reminds us of that. This perspective can help us be more aware and critical of science - looking at it from the outside in - and prevent us from getting too arrogant. We should forget about our prejudices, and appreciate that in the heart of both science and philosophy there is a common aim: to understand the world. In the words of McAllister: “there is a sense in which there is no difference between philosophy and the natural sciences: in their interest for truth, rationality, metaphysical questions”. And perhaps we are coming out of this rough patch in the science and philosophy affair after all. “There was a high point of mistrust in the 80’s and 90’s. But it seems that over the past 20 years, there’s been a bit of a realisation [by scientists] that we [philosophers] also talk sense, and that there are things where we can contribute” says McAllister.

With luck, this is a trend that will catch on. But meanwhile, take it from a scientist, Icke, who knows what he is talking about: “Keep away from a stereotypical view of philosophy. Philosophy is not just chatting about things.”

0 Comments

Add a comment